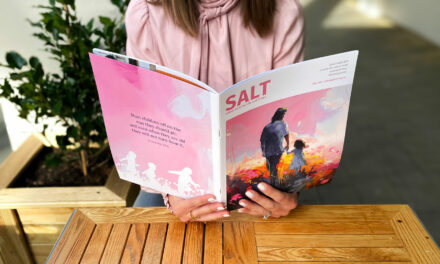

Small Steps, Big Outcomes: Realising our Te Kai Mākona Food Security Strategy

The Salvation Army is changing the way it provides food. Tammie Stroman, Community Ministries kaitohutohu matua (territorial senior advisor for food security), updates SALT on the multi-faceted approach to food security of Te Kai Mākona since its launch in July 2023.

Words Tammie Stroman

He iti hoki te mokoroa nāna i kakati te kahikatea. While the mokoroa grub is small, it cuts through the white pine.

This whakataukī (proverb) speaks of the truth that something much larger can slowly be overcome by something smaller. Similarly, when we think about actualising food security, it can often seem too big to fix. We get overwhelmed by the bigger picture sometimes, weighed by frontline demand and daunted by the long trudge towards systemic change. However, it is our relentless increments that carve out food secure pathways, one small yet mighty step at a time.

There is power in small acts

Our Te Kai Mākona (TKM) food security framework, launched externally in July 2023, envisions all people in Aotearoa New Zealand being fully satisfied, with our Community Ministries being places of support and connection to strengthen food security. The framework focuses on three key pou (pillars): strengthening food provisions to meet the needs of those experiencing food hardship; strengthening food security through additional food supports; and addressing the root causes of food insecurity to transform the broken food systems.

We are the soldiering grubs cutting through white pine, making small strides towards bigger outcomes through community-driven initiatives, localised solutions and collaborative efforts that make significant collective impact. But how do we know if we are making a difference?

Monitoring and evaluation

Global trends suggest as we move through 2024, food security is likely to remain one of the critical challenges for the world to face (Aotearoa included), with a growing proportion of our population indiscriminately experiencing food insecurity. The World Bank has included ‘food and nutrition security’ among the eight global challenges to address at scale, and the United Nations has named their second Sustainable Development Goal (SDG), zero hunger, as being critical to resolving the other 16 Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

At the start of 2024, about every three working days during January, our foodbanks distributed over 1000 healthy food parcels measured against the ‘Aotearoa Food Parcel Measure’ sector standard, with a progressive move towards all our foodbanks offering some form of a choice model. A big focus of Te Kai Mākona is honouring the nutritional adequacy of kai with those we support, although our food security strategy is not about getting better at food parcelling, we want to get better at our responses. This is a conscious pivot of our TKM strategy to manoeuvre towards sustainable food security solutions and away from temporary responses to food insecurity—in part to minimise people’s dependency on external food support.

The annual update of the 2022–2023 New Zealand Health Survey was released at the end of December 2023, with household food insecurity for children revealed to be sitting at 21.3 percent. More than one in three Māori and Pasifika children live in households where food runs out.

By turning our TKM framework into a plan with measurable outcomes that we can evaluate, we ambitiously imagine whānau (families) no longer requiring our foodbanks by 2030, because we are places of support and connection that strengthen food security (aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals that Aotearoa has committed to). This does not negate some level of need we will ultimately continue to respond to, nor does it resolve poverty in its entirety, but it does give our movement an emphasis towards tackling root causes of food insecurity, as well as opportunities to onboard food empowerment initiatives.

In October 2023, the World Bank updated the World Food Security Outlook (WFSO). Published three times a year, the WFSO is an innovative model-based data series designed to monitor and analyse global food security, providing essential information and statistics to help understand the evolving landscape of this sector. The Salvation Army has a wealth of accessible data collection, and we are also in the process of monitoring and evaluating our collective Te Kai Mākona journey.

This will involve expanding on what works to realise our vision by 2030, establishing a collaborative reference group of Te Kai Mākona champions to help us along the journey, and through communities of practice, learning from and sharing with each other—including communications and pānui (newsletters)—to amplify our vision and to uplift our stories.

‘They all ate and were satisfied’

All throughout Aotearoa New Zealand and across the motu (land) our Community Ministries have been making significant practice changes, onboarding a variety of additional food supports to strengthen food security that include Choosing Kai, Buying Kai, Growing Kai, Cooking Kai, Sharing Kai and Partnering and Collaborating around Kai. Through enterprise, innovation and imagination, we are shifting our country towards abundance for all.

In the context of Aotearoa New Zealand, we have plenty of good food available—however, we have a problem with all people having equitable access to that food. Research released by Kore Hiakai Zero Hunger Collective May 2023 highlighted food security barriers that included profit-driven industrial food systems at the expense of local economies and the rising costs of living. Kai in Aotearoa and around the globe is mostly treated as a commodity and not a basic human right, and while ‘access’ in our country can imply a geographical sense, it is mostly related to economics. The story of food insecurity in Aotearoa is not one of food scarcity—it is one of social justice.

Since modernised foodbanks began during the mid-1980s, the distribution of food parcels has helped temporarily address the emergency food needs of those experiencing food hardship, though they do not address the root causes of food insecurity or help to create sustainable food security.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation describes food security as having six facets: availability, access, utilisation, stability, agency and sustainability. ‘Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences.’

While we imagine Aotearoa New Zealand as having a ‘thriving’ population, systemic change related to income, the cost of living and being able to honour nutritional adequacy are integral factors and alternative lenses to use in order to look for longer-term solutions. ‘Thriving’ requires sufficient income to be able to participate fully in one’s community, alongside affordable housing and living costs, with dignified access to enough good food. We know that different parts of people’s lives are affected by food hardships, so any solutions to food insecurity should be developed with these in mind.

The extended definition of the Māori word ‘kai’ from the Kore Hiakai Zero Hunger Collective states that, ‘Kai, as a noun, is food. However, it is also a verb, as consumption is only one part of a cycle that also includes production and distribution. When a whānau has the ability to contribute to and determine the production, sharing and consumption of kai, they are in a state of food security and sovereignty. They are able to determine their choice of, access to, and quality of the kai they consume. A Māori understanding of kai also does not view an individual in isolation. Individuals must be empowered to make choices about their own kai production, distribution and consumption. We are whānau together. To have a system that champions kai is to have one that champions community and champions whenua (land). To look after the people means to look after the whenua.’

In a country that produces a volume of food that could sustain our entire population, part of what will help enable food security is our Community Ministries collaborating and creating the conditions to positively impact local food systems, and by fulfilling our roles as responsible caretakers.

He waka eke noa—we’re all in this together

Referring to our wider organisational commitment to work in unity while leaving no one behind, The Salvation Army Te Ope Whakaora continues to uphold others in compassion, supporting the needs of those most marginalised in communities. As community kai champions, we work relationally through whanaungatanga (relationships), offering places to be seen and held through manaakitanga (hospitality) and by giving service with aroha (love). These values sit at the heart of our Te Kai Mākona framework, as we initiate food security solutions in partnership and work towards impactful common goals.

Every relentless step counts. Whether advocating for policy change, onboarding additional food support and supporting local food initiatives, or spreading awareness and changing our own narratives, every step contributes towards more food secure pathways.

Let us embrace the collective power of the small strides we make by staying committed to the cause and working together: Te Kai Mākona—where all are fully satisfied. Together we can bring transformation for our communities and make Aotearoa New Zealand a food-secure nation.